Discovering Household Travel Data Stories Through Collaboration

In 2020 when we were all starting to work at home, the PSRC data team formed a working group to learn from each other how Household Travel Survey Data could be used to inform urban planning policy. We have used this COVID-19 period to grow our skills in working with household travel survey data.

Thank you to Abdi Mohamud, Brian Lee, Christy Lam, Drew Hanson, Grant Gibson, Neil Kilgren, Polina Butrina, and Mary Richards who shared their brains and time in this effort!

We use GitHub to share scripts with each other. Source: Our Household Travel Survey GitHub repository |

Upskilling Before Discovering

We made many exciting data discoveries during the past year, but before we could really dive into the data, we needed to increase our statistics and scripting skills specific to working with survey data.

We did statistics, learning how to apply sample weights and calculate margins of error.

We wrote functions to easily summarize the data and collaborated via GitHub. Here’s an example of a function we shared with each other:

# Create margins of error for dataset

categorical_moe <- function(sample_size_group){

sample_w_MOE<-sample_size_group %>%

mutate(p_col=p_MOE) %>%

mutate(MOE_calc1= (p_col*(1-p_col))/sample_size) %>%

mutate(MOE_Percent=z*sqrt(MOE_calc1))

sample_w_MOE<- select(sample_w_MOE, -c(p_col, MOE_calc1))

return(sample_w_MOE)

}

Data Discoveries

After we did some upskilling, we were ready to make discoveries on a wide range of hot planning topics like residential displacement, travel by people of color, teleworking, home deliveries, and new mobility.

Discovery Park Source: a picture I took a few years ago |

Residential Displacement

A new question that was asked on the 2019 survey was why people moved from their previous homes. We discovered that:

- About a quarter of households that moved in the past five years within the four-county region reported that they relocated for one or more negative reasons (also called displacement): cost of housing, forced to move, change in income, or loss of community. Cost of housing was by far the top reason.

- One in five white households (22%) felt pressured to leave their homes, as did 14% of Asian households. But nearly one in three (30%) Other People of Color households moved elsewhere because they had to.

- We found that displacement is truly a regional phenomenon. Across the region and its counties, displacement was reported at statistically the same rate (within the margin of error).

If you want more info, we made blog posts about our findings on residential displacement. The Seattle Times wrote story using our data.

Understanding travel by different racial groups

Racial equity is a key part of PSRC’s planning efforts. To analyze people’s travel by race using the survey data we had to figure out how to balance adequate sample sizes with richness of detail about people’s race. At first, we categorized people into three broad groups: Asian Only, non-Hispanic White, and Other People of Color, as in this blog post about travel patterns by race. For example, we reported that “Other People of Color were the most likely to take transit to work (17%), followed by Asians (11%) and whites (9%).”

We realized that although our sample sizes were small, we needed to try to report African American transportation experiences separately because they are so unique and because of the history of oppression on our county. In this later blog post, we specifically analyzed travel by African American people separately. We reported that:

“The survey showed that African American people were much more likely to live in a household with no cars than Non-Hispanic Whites. Around one out of five of African American people lived in a household with no cars, with only about one out of twenty Non-Hispanic Whites having lived in a household with no cars. Asian, Hispanic, and Other race people’s travel behavior generally fell between that of Non-Hispanic Whites and African American people. For example, African American people used transit on 12% of their trips, Asian people used transit on 8% of their trips, Hispanic and Other people use transit on 5% of their trips, and Non-Hispanic Whites use transit on 4% of their trips.”

Also, we encountered a puzzle in terms of how to describe household races: How do we describe a household’s race? Not only are people multi-racial, households are also multi-racial. Residential choices and vehicle ownership choices are really made at a household level, as opposed to by individuals in the household, and so we need to summarize data at a household level. The Census uses this antiquated term of householder to describe household races.

Our work assigned households to racial categories as follows. Based on the composition of adults and the person-level categorization, each household was assigned to one of the following household racial categories:

- African American – all adults are in the African American group; OR a mix of adults in the African American and White groups.

- Asian – all adults are in the Asian group; OR a mix of adults in the Asian and White groups.

- Hispanic – all adults are in the Hispanic group; OR a mix of adults in the Hispanic and White groups.

- Missing – any or all adults are in the Missing group.

- Non-Hispanic White – all adults are in the White group.

- Other – all adults are in the American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

See this technical note on how we defined household race.

Telework Patterns

Telework was a hot topic in the past year, since there has been a necessary surge in the behavior, so we looked into what the data told us about pre-COVID telework behavior. The 2019 household travel survey asked, “How much did you work at home or telework for pay on your travel date? Here’s some things we found:

- 10% of workers teleworked between 6 and 12 hours a day. More workers teleworked (14%) less the six hours but more than zero.

- People who teleworked part-time traveled 10% fewer miles by car during their average day; people who teleworked full time traveled 34% less distance by car.

- The number of trips people who teleworked made was similar to those who did not. They had shorter trips in general, that is why their car distance is reduced. People substituted non-work trips for work trips.

- Young people (18-24 years old) teleworked full-time less frequently compared with other age groups.

- For the people with the household income of $150,000 or more, the odds of being more likely to teleworked were 30% higher than other income categories.

- There is no difference in genders between the share of workers who teleworked. (More men work, however, so males represent a higher share of teleworkers [63%].)

- Hispanic and Asian workers were 20% to 30% higher than Whites to telework. African American workers were 25% less likely to telework than Whites.

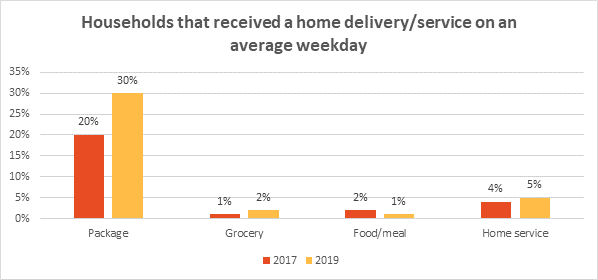

Home deliveries

As the number of home deliveries has appeared to increase dramatically over the past few years, we were interested to see what the travel survey data could tell us. The travel survey asked if households received packages or were delivered groceries on a given day. We found that in 2019, home deliveries were common and increasing. One out of three households received a package on an average weekday.

My daughter getting a delivery from Gram. |

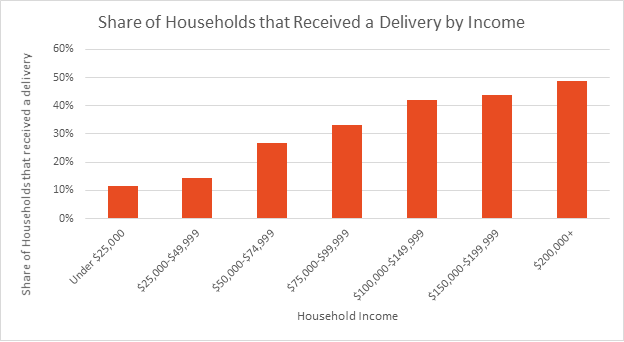

The Seattle Times also reported on the travel survey home deliveries data. The following charts show the trend in deliveries and that high income households received many more deliveries than low income ones.

Household Travel Survey Deliveries 2017 and 2019 |

Household Travel Survey Deliveries by Income |

New mobility

Pre-COVID, new mobility (also known as ride-hailing and carsharing) was a hot topic. I’m sure it will come back.

We found that from 2017 to 2019, the share of regional adults who had ever used a ride-hailing service for travel went up from 24% to 35%. The share of Seattle adults who had used a ride-hailing service is substantially higher than the region as a whole. From 2017 to 2019, the share of Seattle adults who had ever used a ride-hailing service had increased from from 44% to 55%. In other words, over half of Seattle adults had used ride-hailing in 2019.

People who use ride-hailing and car share services have exhibit different travel behavior than the general Puget Sound population. Around 73% of ride-hailing and carsharing users commuted by walking/biking, carpool, or transit. In comparison, more than 70% of regional workers use a single-occupancy vehicle (SOV) on their commute.

Commuting Behavior

Transportation planners are often interested in commuting behavior. Our survey data helps to break common misconceptions around commuting.

For example, trips to or from work are only 24% of all weekday trips.

We’ve also heard speculation that lower income workers have to travel further than higher income workers to get to work as housing prices rise. The data shows, however, that:

From workers with incomes less than $75,000 annually, lower income workers have shorter commutes.Workers with incomes under $10,000 have commutes of around 14 minutes, whereas workers with incomes from $50,000-$74,999 have commutes around 27 minutes. The average travel time to work is about the same for workers in households with incomes greater than $75,000 – it’s around 33 minutes.

Model Estimation

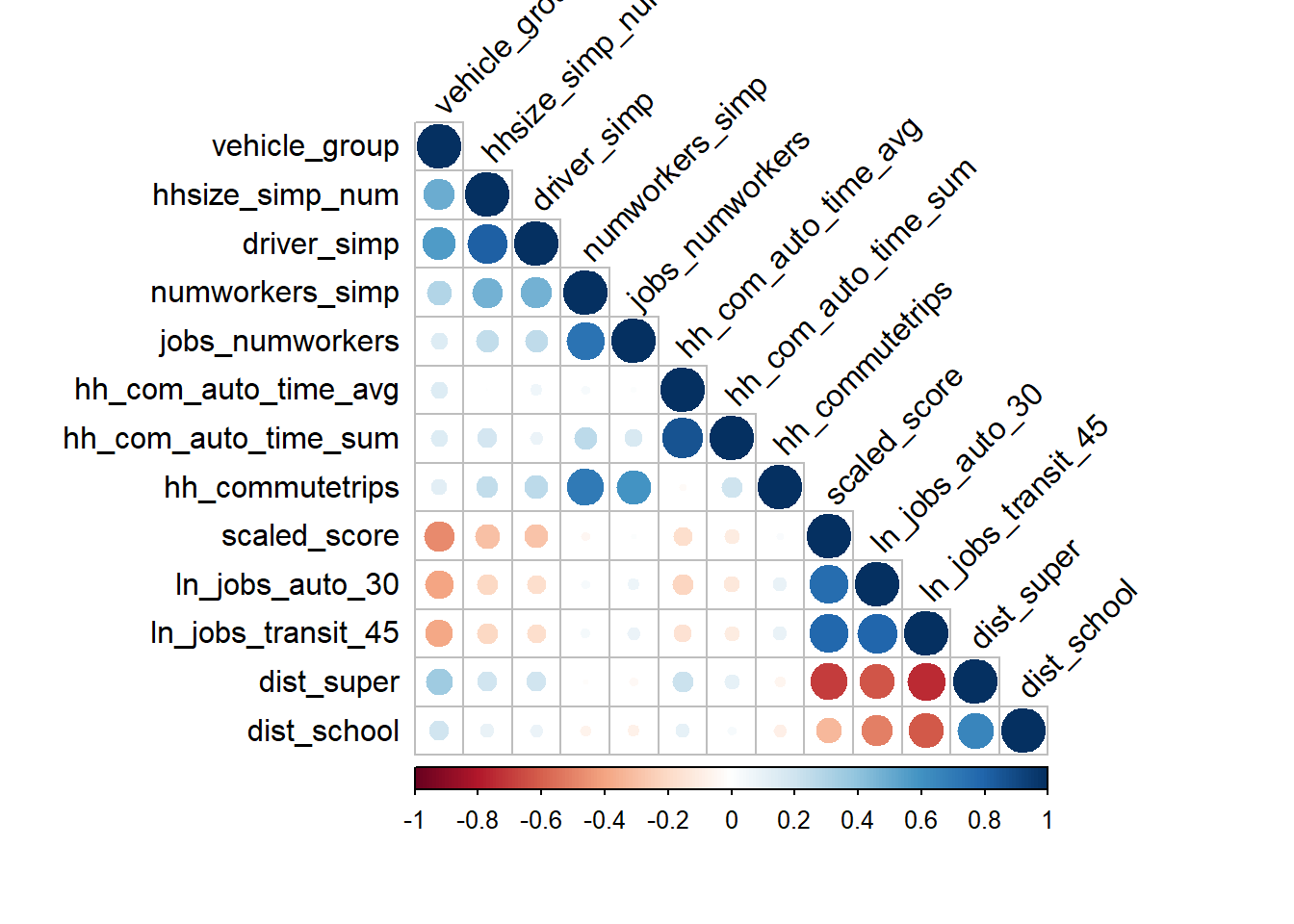

After a while of working with the data, we realized that looking at data on one or two dimensions really doesn’t tell the whole story. We wanted to be able control for multiple factors to determine what variables had the strongest correlation with different behaviors. We estimated models to find what factors are driving behaviors. Some of code to estimate models is up here on Github.

This graphic shows the correlation matrix of variables in the auto ownership model. We use R for model estimation. Source: Mary Richards, auto ownership estimation |

The models looked at questions like:

- Do people who telework on a given day travel less? (Yes)

- Do people who live in places with pro-growth policies experience less residential displacement? (Yes)

- Do people who get home deliveries make fewer shopping trips on an average weekday? (Not that we could observe)

- Does transit access correlate with lower houeshold vehicle ownership, all else being equal (controlling for income, household size, etc)? (Yes definitely)

Let’s do this again sometime!

I hope we can form more working groups to build pathways from raw data through statistics to urban planning meaning. Data people tend to be introverts and often want to stay in their data corner by themselves. But when we work together our code improves, our statistical analysis has more rigor, and we are more useful to the planning process.